George Washington – first American president, commander of the Continental Army, president of the Constitutional Convention, and farmer. Through these roles, Washington exemplified character and leadership.

Childhood and Education

George Washington was born at his family's plantation on Popes Creek in Westmoreland County, Virginia, on February 22, 1732, to Augustine and Mary Ball Washington. George's father was a leading planter in the area and served as a justice of the county court.

Augustine Washington's first wife, Jane Butler, died in 1729, leaving him with two sons, Lawrence and Augustine, Jr., and a daughter, Jane. George was the eldest of Augustine and Mary's six children: George, Elizabeth, Samuel, John Augustine, Charles, and Mildred.

Ferry Farm

Around 1734, the family moved up the Potomac River to another Washington property, Little Hunting Creek Plantation (later renamed Mount Vernon). In 1738, they moved again to Ferry Farm, a plantation on the Rappahannock River near Fredericksburg, Virginia, where George spent much of his youth.

Little is known of George Washington's childhood, and it remains the most poorly understood part of his life. When he was eleven years old, his father Augustine died, leaving most of his property to George's adult half brothers. The income from what remained was just sufficient to maintain Mary Washington and her children. As the oldest of Mary's children, George undoubtedly helped his mother manage the Rappahannock River plantation where they lived. There he learned the importance of hard work and efficiency.

Washington's Education

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Washington never attended college or received a formal education. His two older half brothers, Lawrence and Augustine, attended Appleby Grammar School in England. However, after the death of their father, the family limited funds for education. Private tutors and possibly a local school in Fredericksburg provided George and his siblings with the only formal instruction he would receive.

In addition to reading, writing, and basic legal forms, George studied geometry and trigonometry—in preparation for his first career as a surveyor—and manners—which would shape his character and conduct for the rest of his life.

The Rules of Civility and Decent Behaviour

Before the age of sixteen, George Washington copied out the 110 rules covered in The Rules of Civility and Decent Behaviour. This exercise, now regarded as a formative influence in the development of his character, included guidelines for behavior and general courtesies.

Slavery

Like most elite Americans, the Washingtons were deeply entangled in a global commercial system that revolved around slavery. The vast network of 18th-century transatlantic trade involved the flow of manufactured goods from Europe, enslaved people from Africa, and raw materials from the Americas.

The economy and social structure of Washington’s native Virginia depended on the labor of enslaved Africans and their descendants to cultivate cash crops like tobacco. Slavery was an integral part of Washington’s life from an early age.

At age 11, he inherited 10 enslaved people from his father. He would go on to inherit, purchase, rent, and gain control of more than 500 enslaved people at Mount Vernon and his other properties by the end of his life.

When he married widow Martha Dandridge Custis in 1759, she brought 84 enslaved people to Mount Vernon as part of her “dower share” of her first husband’s estate. She retained life rights to these people but did not legally own them. By 1799, the number of “dower slaves” at Mount Vernon had grown to 153 through natural increase, as children inherited the status of their mother.

Washington’s views on slavery changed over time. Economic and moral concerns led him to question slavery after the Revolutionary War, though he never lobbied publicly for abolition. Unable to extricate himself from slavery during his lifetime, Washington chose to free the 123 enslaved people he owned outright in his will.

Surveying

During George Washington’s early teenage years, he completed many school exercises in penmanship, comportment, and mathematics. Some exercises, such as the Art of Surveying and Measuring Land, provided instruction for practice surveys and included samples taken directly from William Leybourn's The Compleat Surveyor of 1657. The formal training Washington received in surveying was complemented by practical experience in the field.

In the mid-1740s, Washington surveyed five acres for A Plan of a Piece of Meadow called Hell Hole, Situate on the Potowmack near Little Hunting Creek. Along with many other plats, Washington drew A Plan of Major Law[rence] Washington's Turnip Field.

In 1748 Washington was invited to join a survey party organized by his neighbor and friend George William Fairfax of Belvoir. Fairfax assembled an experienced team to layout lots within a large tract along the western frontier of Virginia. Over their month-long expedition, Washington learned even more about surveying and gained important experience of living on the frontier.

Washington's career as a professional surveyor began in 1749. He received a commission as a surveyor for the newly formed Culpeper County, probably at the behest of William Fairfax who was then serving on the Governor's Council.

French and Indian War

In 1753, the Governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie, learned that French troops had moved south from Canada and were constructing forts in the region south of Lake Erie, an area claimed by the British (now in Western Pennsylvania). Both France and England recognized the commercial potential of the region. French trappers had been working in the area for some time. Dinwiddie was concerned that the French troops would also fortify the forks of the Ohio River -- the strategic point where the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers join to form the Ohio River. This point, now Pittsburgh, was the eastern gateway to the Ohio River Valley.

Allegheny Expedition

In the fall of 1753, Dinwiddie sent 21-year-old Major Washington to deliver a message to the French, demanding they leave the area. Today, this journey is known as the Allegheny Expedition and Washington was aided by Christopher Gist, a frontier guide, and local Native Americans. The party finally reached the French post at Fort Le Boeuf on the evening of December 11, escorted by Seneca chief Tanacharison (Half-King), two Iroquois chiefs, and one from the Delaware Nation.

The return trip tested Washington's endurance. He hiked for days through snowy woods, fell off a raft into the ice-choked Allegheny River, nearly drowned, and was forced to spend a freezing night on an island without shelter. Washington's account of the arduous 900-mile journey was published by Governor Dinwiddie in both Williamsburg and London, establishing an international reputation for George Washington by the time he was 22.

Jumonville Glen Skirmish

A few months later Dinwiddie dispatched Washington, now a lieutenant colonel, and some 150 men to assert Virginia's claims on the land. As they advanced, Washington's men skirmished with French soldiers, killing 10 men, including the French commander, Joseph Coulon de Villiers, Sieur de Jumonville. Washington then retreated to an ill-placed and makeshift palisade he called Fort Necessity. He was forced to surrender when the French surrounded the fort. The campaign ended in humiliation for Washington and ignited the French and Indian War.

General Braddock

Although he resigned his commission after the surrender, Washington returned to the frontier in 1755 as a volunteer aide to General Edward Braddock. Braddock had been sent by the King of England to drive the French from the Ohio Country. Braddock's army was routed near the Monongahela River and fled in confusion to Virginia. During the battle, while attempting to rally the British soldiers, Washington had two horses shot out from under him and four bullet holes shot through his coat. Although he behaved with conspicuous bravery, Washington could do little except lead the broken survivors to safety.

In recognition of his conduct, Washington was given command of Virginia's entire military force. With a few hundred men he was ordered to protect a frontier some 350 miles long. Although this was a frustrating assignment, it provided him with experience in commanding troops through an arduous campaign. In 1758 the British finally took the forks of the Ohio. Peace returned to Virginia, and Washington resigned his commission to return to Mount Vernon, his duty faithfully performed.

House of Burgesses

The first time George Washington ran for public office, he lost. However, he won his second race and served in the Virginia House of Burgesses from 1758 until 1776.

Marriage and Family

Martha Washington served as the nation's first first lady and spent about half of the Revolutionary War at the front. She helped manage and run her husbands' estates. She raised her children, grandchildren, nieces, and nephews; and for almost 40 years she was George Washington's "worthy partner".

On January 6, 1759, George Washington and Martha Dandridge Custis married, she was 27 years old and from the Tidewater area of Virginia. Martha was a widow and after the death of her first husband, Daniel Parke Custis, she assumed control of considerable property (in the form of land and enslaved people). She also had two young children, John known as “Jacky” and Martha called “Patsy”.

In addition to seeing to her children's education, Martha oversaw the domestic staff of hired and enslaved butlers, housekeepers, maids, cooks, waiters, laundresses, spinners, seamstresses, and gardeners. These happy years at Mount Vernon were tragically interrupted, in 1773, when 17-year-old Patsy had a seizure and died.

Revolutionary War

During the Revolutionary War, George Washington was always leading the army, so Martha Washington along with the helped of her husband’s cousin managed Mount Vernon. She also spent almost half of the war in camp; entertaining visiting colonial and international officials and prominent civilians. She helped copy correspondences, knitted for the soldiers, and made hospital visits. As the war came to an end, much of the happiness was drowned out for Martha Washington by the loss of her son, John, who died of camp fever at Yorktown.

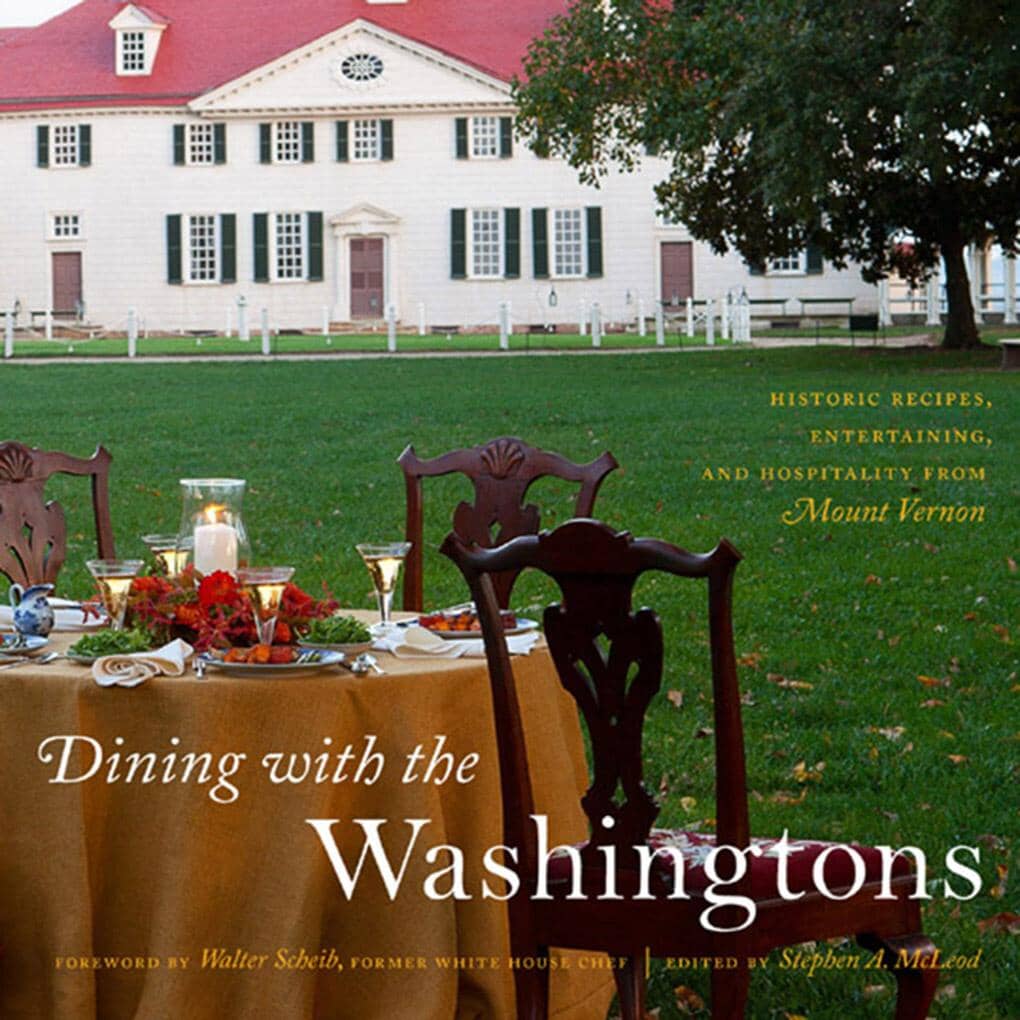

First Family

After the war, the Washingtons returned to Mount Vernon to rebuild their plantation and raise John’s two youngest children, Eleanor and George. In 1789, the Washingtons, who were in their late 50s, became the first first family. Martha Washington oversaw much of the official entertaining, hosting a weekly dinner on Thursdays and a reception on Fridays, in addition to many other frequent visitors.

Eight years later, the Washingtons retired to their beloved Mount Vernon. Over the next two years, they improved their home and welcomed many friends. Then on December 14, 1799, George Washington died. Martha Washington was devastated and told several people she was ready to join him in death. After an illness of several weeks, Martha Washington died on May 22, 1802. She was 70 years old. In newspapers throughout the country, Martha Washington was eulogized as "the worthy partner of the worthiest of men."

The Life of Martha Washington

This is the story of Martha Washington, the worthiest of partners to the worthiest of men.

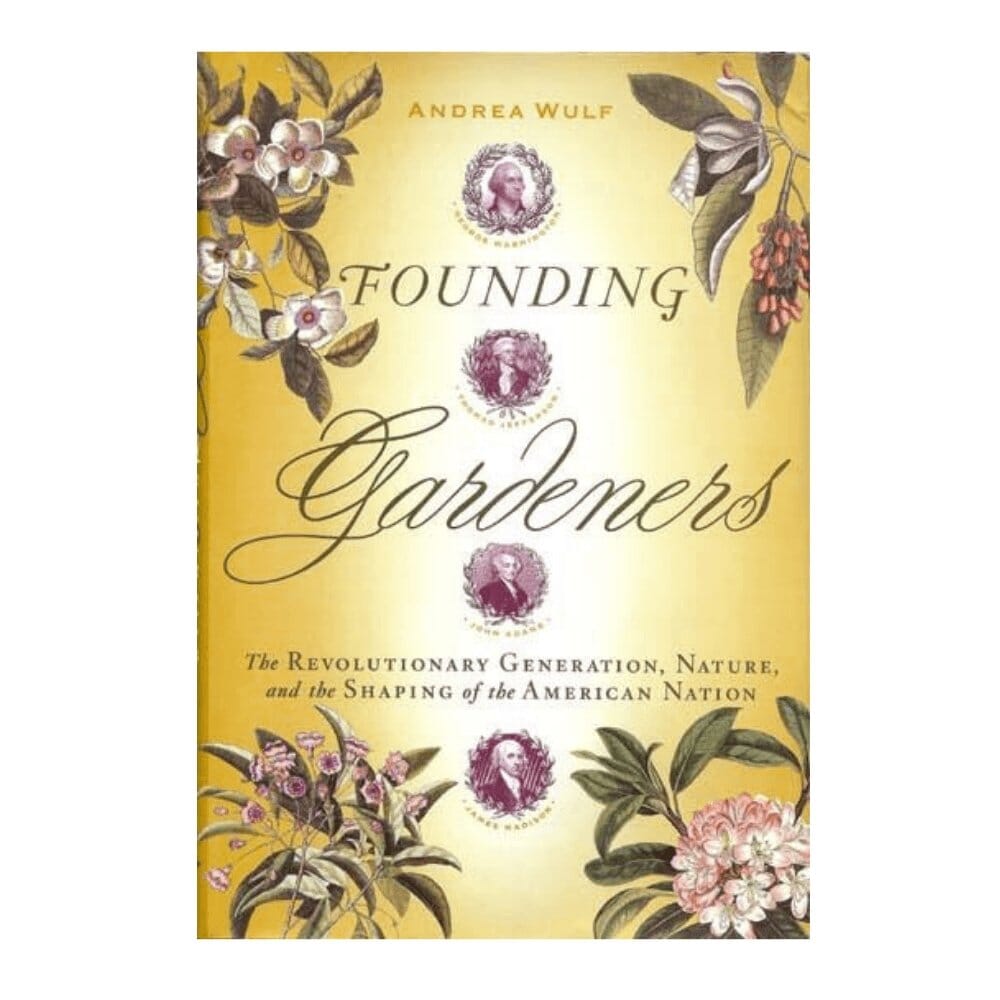

Entrepreneur

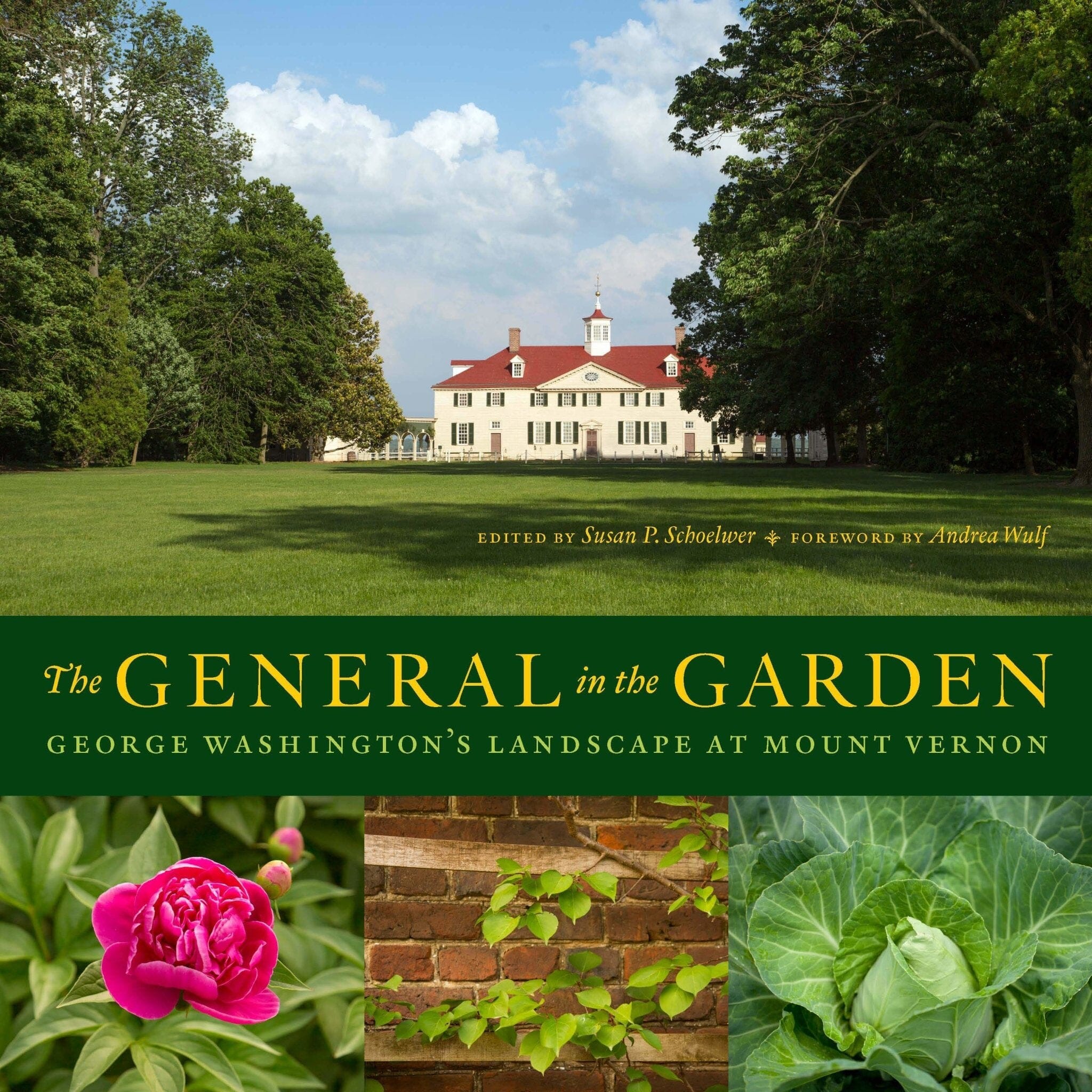

George Washington spent the years between 1759 and 1775 overseeing the farms at Mount Vernon. Washington worked constantly to improve and expand the mansion house and its surrounding plantation. He established himself as an innovative farmer, who switched from tobacco to wheat as his main cash crop in the 1760's. In an effort to improve his farming operation, he diligently experimented with new crops, fertilizers, crop rotation, tools, and livestock breeding. He also expanded the work of the plantation to include flour milling and commercial fishing in an effort to make Mount Vernon a more profitable estate.

Over the years, Washington had his house enlarged. First the roof was raised to create a third floor. Later a wing was added to each end, had a piazza built overlooking the Potomac River, and his vision was crowned with a cupola. By the time of his death in 1799, he had expanded the plantation from 2,000 to 8,000 acres consisting of five farms, with more than 3,000 acres under cultivation.

Shortly after taking up wheat as his main cash crop, Washington built a large gristmill outfitted with two pairs of millstones. One pair of stones ground corn into meal for use at Mount Vernon and the other ground wheat into superfine flour for export to foreign ports. Washington also began making whiskey on the advice of his farm manager, James Anderson, a trained distiller from Scotland. He soon built one of the largest distilleries in America. At its peak, Washington’s distillery produced over 11,000 gallons of rye whiskey, becoming one of his most successful enterprises.

Even as President, Washington’s thoughts often turned to Mount Vernon. For example, while in office, he designed a 16-sided barn to thresh wheat in a more efficient and sanitary way. As horses circled the second floor, they treaded on the wheat that had been spread there, breaking the grain from the chaff. The wheat would fall through gaps in the floorboards to the first floor, where it was winnowed. After winnowing, the grain was taken to the gristmill and ground into flour. From the President’s House in Philadelphia, Washington followed the barn’s construction every step of the way. He even correctly calculated the number of bricks needed for the first floor – which turned out to be exactly 30,820!

The Working Gristmill at Mount Vernon

Take a look into the operation of the George Washington's automated gristmill.

Watch the videoRevolutionary War

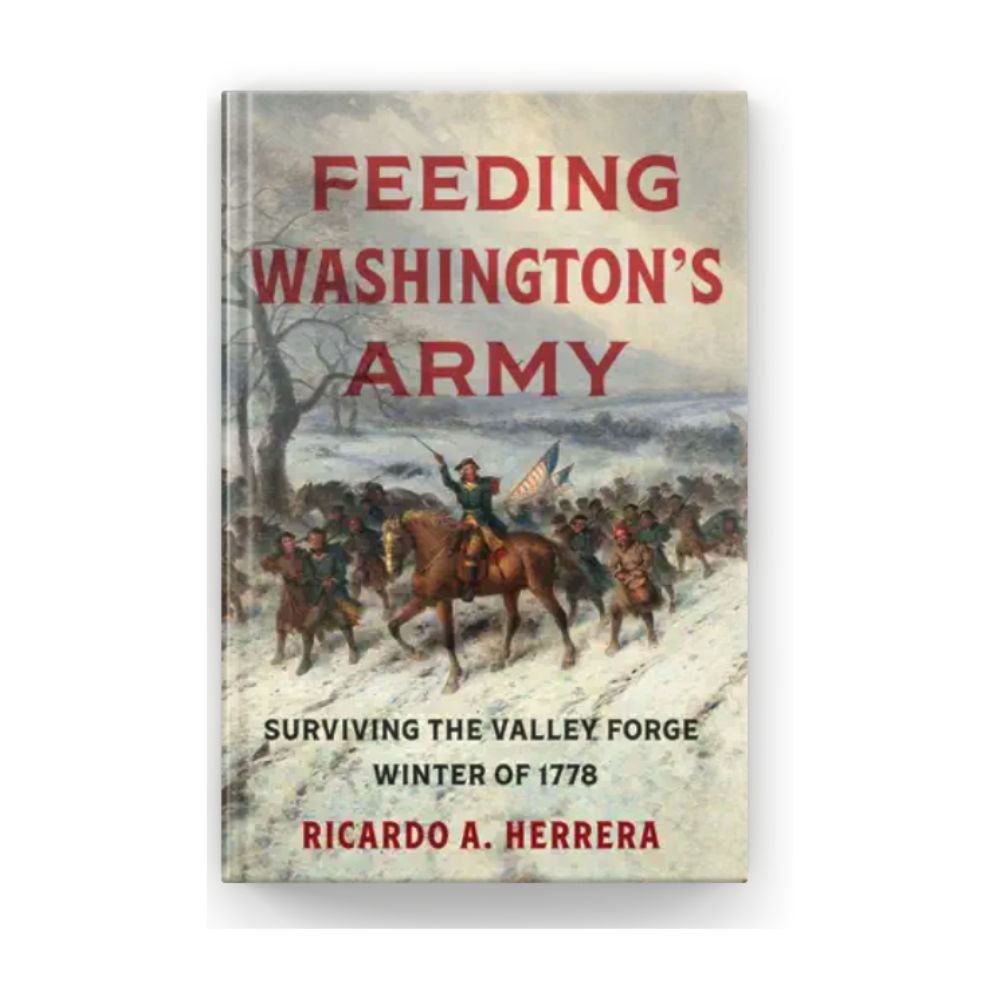

In June 1775, Congress commissioned George Washington to take command of the Continental Army besieging the British in Boston. He wrote home to Martha that he expected to return safely to her in the fall. The command kept him away from Mount Vernon for more than 8 years (with only one very brief visit while en route to Yorktown).

It was a command for which his military background, although greater than that of any of the other available candidates, hardly prepared him. His knowledge lay in frontier warfare, involving relatively small numbers of soldiers. He had no practical experience maneuvering large formations, handling cavalry or artillery, or maintaining supply lines adequate to support thousands of men in the field. He learned on the job; and although his army reeled from one misfortune to another, he had the courage, determination, and mental agility to keep the American cause one step ahead of complete disintegration until he figured out how to win the unprecedented revolutionary struggle he was leading.

His task was not overwhelming at first. The British position in Boston was untenable, and in March 1776 they withdrew from the city. But it was only a temporary respite. In June a new British army, under the command of Sir William Howe, arrived in the colonies with orders to take New York City. Howe commanded the largest expeditionary force Britain had ever sent overseas.

Defending New York was almost impossible. An island city, New York is surrounded by a maze of waterways that gave a substantial advantage to an attacker with naval superiority. Howe's army was larger, better equipped, and far better trained than Washington's. They defeated Washington's army at Long Island in August and routed the Americans a few weeks later at Kip's Bay, resulting in the loss of the city. Forced to retreat northward, Washington was defeated again at White Plains. The American defense of New York City came to a humiliating conclusion on November 16, 1776, with the surrender of Fort Washington and some 2,800 men. Washington ordered his army to retreat across New Jersey. The remains of his forces, mud-soaked and exhausted, crossed the Delaware River into Pennsylvania on December 7.

The British had good reason to believe that the American rebellion would be over in a few months and that Congress would seek peace rather than face complete subjugation of the colonies. The enlistments of most of Washington's army were due to expire at the end of December. However, instead of crushing the remains of Washington's army, Howe went into winter quarters, with advanced garrisons at Trenton and Princeton, leaving Washington open to execute one of the most daring military operations in American history. On Christmas night Washington's troops crossed the Delaware River and attacked the unsuspecting garrison at Trenton, forcing it to surrender. A few days later Washington again crossed the Delaware, outmaneuvered the force sent to crush him, and fell on the enemy at Princeton, inflicting a humiliating loss on the British.

For much of the remainder of the war, Washington's most important strategic task was to keep the British bottled up in New York. Although he never gave up hope of retaking the city, he was unwilling to risk his army without a fair prospect of success. An alliance with France and the arrival of a French army under the Comte de Rochambeau in July 1780 renewed Washington's hopes to recapture New York; however, together Washington and Rochambeau commanded about 9,000 men -- some 5,000 fewer than Clinton. In the end, therefore, the allied generals concluded, that an attack on New York could not succeed.

Instead, they decided to strike at the British army under Cornwallis, which was camped at Yorktown, Virginia. Washington's planning for the Battle of Yorktown was as bold as it had been for Trenton and Princeton but on a much larger scale. Depending on Clinton's inactivity, Washington marched south to lay siege on Cornwallis. On October 19, 1781, he accepted the surrender of Cornwallis's army. Although two more years passed before a peace treaty was completed, the victory at Yorktown effectively brought the Revolutionary War to an end.

To the world's amazement, Washington had prevailed over the more numerous, better supplied, and fully-trained British army, mainly because he was more flexible than his opponents. He learned that it was more important to keep his army intact and to win an occasional victory to rally public support than it was to hold American cities or defeat the British army in an open field. Over the last 200 years, revolutionary leaders in every part of the world have employed this insight, but never with a result as startling as Washington's victory over the British.

On December 23, 1783, Washington presented himself before Congress in Annapolis, Maryland, and resigned his commission. Like Cincinnatus, the hero of Classical antiquity whose conduct he most admired, Washington had the wisdom to give up power when he could have been crowned a king. He left Annapolis and went home to Mount Vernon with the fixed intention of never again serving in public life. This one act, without precedent in modern history, made him an international hero.

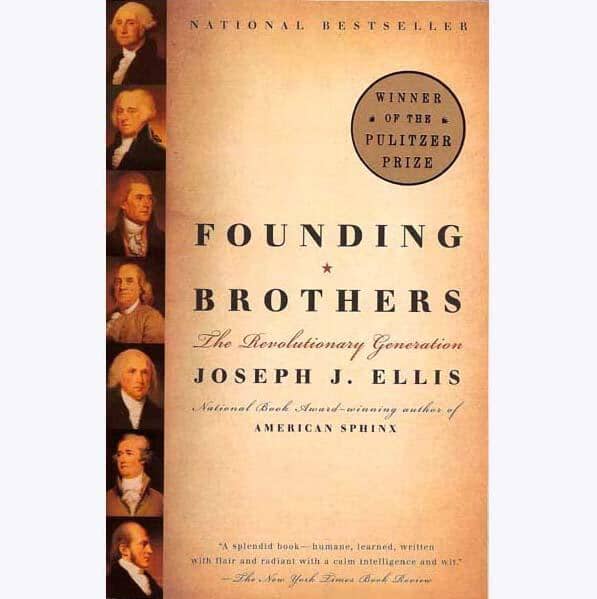

A More Perfect Union: George Washington and the Creation of the U.S. Constitution

Most popular revolutions throughout history have descended into bloody chaos or fallen under the sway of dictators. So how did the United States, born of its own 8-year revolution, ultimately avoid these common pitfalls?

Constitutional Convention

Although Washington longed for a peaceful life at Mount Vernon, the affairs of the nation continued to command his attention. He watched with mounting dismay as the weak union created by the Articles of Confederation gradually disintegrated, unable to collect revenue or pay its debts. He was appalled by the excesses of the state legislatures and frustrated by the diplomatic, financial, and military impotence of the Confederation Congress. By 1785 Washington had concluded that reform was essential. What was needed, he wrote to James Madison, was an energetic Constitution.

In 1787, Washington ended his self-imposed retirement and traveled to Philadelphia to attend a convention assembled to recommend changes to the Articles of Confederation. He was unanimously chosen to preside over the Constitutional Convention, a job that took four months. He spoke very little in the convention, but few delegates were more determined to devise a government endowed with real energy and authority. My wish, he wrote, is that the convention may adopt no temporizing expedients but probe the defects of the Constitution to the bottom and provide a radical cure.

After the convention adjourned, Washington's reputation and support were essential to overcome opposition to the ratification of the proposed Constitution. He worked for months to rally support for the new instrument of government. It was a difficult struggle. Even in Washington's native Virginia, the Constitution was ratified by a majority of only one vote.

Once the Constitution was approved, Washington hoped to retire again to private life. But when the first presidential election was held, he received a vote from every elector. He remains the only President in American history to be elected by the unanimous voice of the people.

Washington's World Interactive Map

George Washington traveled far and wide during his lifetime. Our Washington's World Interactive Map will help you discover all the journeys and places that Washington visited.

President of the United States

Washington served two terms as President. His first term (1789-1793) was occupied primarily with organizing the executive branch of the new government and establishing administrative procedures that would make it possible for the government to operate with the energy and efficiency he believed were essential to the republic's future. An astute judge of talent, he surrounded himself with the most able men in the new nation. He appointed his former aide-decamp, Alexander Hamilton, as Secretary of the Treasury; Thomas Jefferson as Secretary of State; and his former artillery chief, Henry Knox, as Secretary of War. James Madison was one of his principal advisors.

In his First Inaugural Address, Washington confessed that he was unpracticed in the duties of civil administration; however, he was one of the most able administrators ever to serve as President. He administered the government with fairness and integrity, assuring Americans that the President could exercise extensive executive authority without corruption. Further, he executed the laws with restraint, establishing precedents for broad-ranging presidential authority. His integrity was most pure, Thomas Jefferson wrote, his justice the most inflexible I have ever known, no motive of interest or consanguinity, friendship, or hatred, being able to bias his decision. Washington set a standard for presidential integrity rarely met by his successors, although he established an ideal by which they all are judged.

During Washington's first term the Federal Government adopted a series of measures proposed by Alexander Hamilton to resolve the escalating debt crisis and established the nation's finances on a sound basis, concluded peace treaties with the southeastern Indian tribes, and designated a site on the Potomac River for the permanent capital of the United States. But as Washington's first term ended, a bloody Indian war continued on the northwestern frontier. The warring tribes were encouraged by the British, who retained military posts in the northwest. Further, the Spanish denied Americans use of the Mississippi River. These problems limited the westward expansion to which Washington was committed.

Growing partisanship within the government also concerned Washington. Many men in the new government -- including Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and other leaders of the emerging Republican party -- were opposed to Hamilton's financial program. Washington despised political partisanship but could do little to slow the development of political parties.

During his first term Washington toured the northern and southern states and found that the new government enjoyed the general support of the American people. Convinced that the government could get along without him, he planned to step down at the end of his first term. But his cabinet members convinced him that he alone could command the respect of members of both burgeoning political parties. Thomas Jefferson visited Washington at Mount Vernon to urge him to accept a second term. Although longing to return home permanently, Washington reluctantly agreed.

Washington's second term (1793-1797) was dominated by foreign affairs and marred by a deepening partisanship in his own administration. Washington assumed the Presidency on the eve of the French Revolution, a time of great international crisis. The outbreak of a general European war in 1793 forced the crisis to the center of American politics. Washington believed the national interest of the United States dictated neutrality. War would be disastrous for commerce and shatter the nation's finances. The country's future depended on the increase in wealth and opportunity that would come from commerce and westward expansion. One of Washington's most important accomplishments was keeping the United States out of the war, giving the new nation an opportunity to grow in strength while establishing the principle of neutrality that shaped American foreign policy for more than a century. Although Washington's department heads agreed that the United States should remain neutral, disagreements over foreign policy aggravated partisan tensions among them. The disagreements were part of the deepening division between Federalists and Republicans. Opposition to federal policies developed into resistance to the law in 1794 as distillers in Western Pennsylvania rioted and refused to pay taxes. Washington directed the army to restore order, a step applauded by Federalists and condemned by Republicans.

Despite Washington's disappointment with the rise of partisanship, the last years of his Presidency were distinguished by important achievements. The long Indian war on the northwest frontier was won, Britain surrendered its forts in the northwest, and Spain opened the Mississippi to American commerce. These achievements opened the West to settlement. Washington’s Farewell Address helped to summarize many of Washington’s strongest held beliefs about what it would take to sustain and grow the young nation that he helped found.

Supreme Court Justice Kennedy on Washington's Presidency

Justice Kennedy talks about the role Washington played in establishing the office of the president.

Watch the videoRetirement

Finally retired from public service, George and Martha Washington returned to their beloved Mount Vernon where they would spend their final years.

On Thursday, December 12, 1799, George Washington was out on horseback supervising farming activities from late morning until three in the afternoon. The weather shifted from light snow to hail and then to rain. Upon Washington's return it was suggested that he change out of his wet riding clothes before dinner. Known for his punctuality, Washington chose to remain in his damp attire.

Washington recognized the onset of a sore throat and became increasingly hoarse. After retiring for the night Washington awoke in terrible discomfort at around two in the morning. Martha was concerned about his state and wanted to send for help. Tobias Lear, Washington’s secretary, sent for George Rawlins, an overseer at Mount Vernon, who at the request of George Washington bled him. Lear also sent to Alexandria for Dr. James Craik, the family doctor and Washington's trusted friend and physician for forty years. As Washington’s condition worsened, two additional doctors were sent for and arrived at Washington’s bedside.

Despite receiving a regimen of blood-lettings, induced vomiting, an enema, and potions of vinegar and sage tea, Washington’s condition worsened. Washington called for his two wills and directed that the unused one should be burned.

The Death of George Washington

Between ten and eleven at night on December 14, 1799, George Washington passed away. He was surrounded by people who were close to him including his wife who sat at the foot of the bed, his friends Dr. Craik and Tobias Lear, enslaved housemaids Caroline Branham, Molly, and Charlotte, and his valet Christopher Sheels who stood in the room throughout the day.

According to his wishes, Washington was not buried for three days. During that time his body lay in a mahogany casket in the New Room. On December 18, 1799 a solemn funeral was held at Mount Vernon and he was laid to rest in the family tomb.

Washington's Will

In his will, written several months before his death in December 1799, George Washington left directions for the emancipation of all the slaves that he owned, after the death of Martha Washington.

![One of the most important tools of the trade was a surveyor's compass. When mounted on a staff, the compass enabled the user to establish a line from a known reference point to the point of interest and determine its bearing. MVLA [W-579/A-B]](https://mtv-drupal-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/files/styles/text_image_block/s3/callout/text-image-block-full/image/sml_surveying-gear-web.jpg.webp?VersionId=Ffb1FYzTM1a7fqA5IxyGYUX8vm2qFeH2&itok=vR45R54i)