Mount Vernon had the chance to sit down with James Kirby Martin, author of Benedict Arnold, Revolutionary Hero: An American Warrior Reconsidered (order online), and Cullen University Professor of history at the University of Houston, to discuss the heroism and treachery of Benedict Arnold during the Revolutionary War.

Did George Washington and Benedict Arnold know and admire each other?

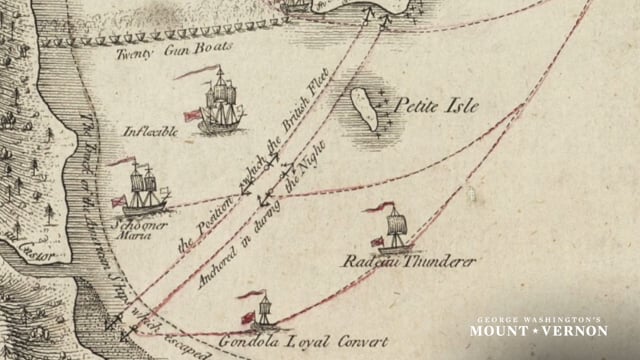

Yes, at least at the outset of the war. Benedict Arnold and George Washington first met in August of 1775 after Washington had taken command of the newly formed Continental army outside Boston in Cambridge, MA. Because of Arnold’s management both in taking and keeping Fort Ticonderoga back in May-June 1775, Washington decided to ask Arnold to lead a column into Canada to take Quebec City and bring that province into the rebellion. Arnold did so with aplomb but suffered a serious wound on the last day of 1775 in a failed attempt to capture that city. Benedict Arnold went on to fight successfully in 1776 in keeping the British from invading the colonies through the Lake Champlain region, and his greatest victory was at Saratoga in 1777, which led to the French coming into the war as the American’s first and most important allies. Washington thought of Arnold as his “fighting general,” and supported him as much as he could up to the time of Benedict Arnold’s defection back to the British on Sept. 25, 1780. One wonders if Benedict Arnold had served directly under George Washington’s command instead of detached operations whether his rejection of the American cause might have taken place.

Videos: Benedict Arnold

Learn more from the experts

Was Benedict Arnold really a battlefield hero early in the Revolutionary War?

Absolutely, yes. His performance in taking and holding Fort Ticonderoga, invading Canada, delaying the British advance on Lake Champlain in 1776 (Arnold’s performance during the Battle at Valcour Island on Oct. 11 was a masterful example of brilliant leadership), and at Saratoga in Sept.-Oct. 1777 made him an invaluable asset to the American cause. Washington knew this was the case, realized Benedict Arnold’s value, and did what he could to support Arnold, even when a foolish Continental Congress passed over Arnold for promotion to major general in 1777 in favor of five mediocre (in two cases likely incompetent) brigadiers junior to Arnold in seniority of service.

Breymann Redoubt

Arnold's brave attack on the rear of this Hessian position at Saratoga helped to secure an important victory.

How did Arnold’s wounds from the Battle of Saratoga factor into his path towards betrayal of the American cause?

Definitely a factor. Seriously wounded in the same leg in which he had taken his first terrible wound at Quebec, Benedict Arnold was angry and peevish during more than four months in a patriot military hospital in Albany, NY. He had plenty of time to think how much suffering he was going through after having been passed over for higher rank, a burning insult to is good name as a virtuous patriot, and in addition to how much he had sacrificed in terms of using his own wealth to support the American cause.

Moreover, he had forsaken his lucrative career as a merchant/trader operating out of New Haven, CT. Congress had restored his rank before Saratoga but not his seniority. When Washington wrote a still suffering Benedict Arnold in Jan. 1778, after the great victory at Saratoga, that Congress had finally restored his seniority, Arnold did not immediately respond. He was furious that Congress had cast a medal to Horatio Gates as the alleged “hero of Saratoga” when Arnold had actually provided the field leadership in both battles leading the Americans to victory.

When Benedict Arnold did respond to Washington, he said that he wished the commander in chief well in his “arduous task” of “seeing peace and happiness restored to your country on the most permanent basis.” In his mounting disillusionment, Arnold was separating himself from a cause in which he was losing his faith. He sent this letter to Washington in March 1778, two and a half years before he gave up completely on the American cause.

Do you think that Arnold’s betrayal was inevitable? What forces led him down this path?

Certainly not in 1775. Benedict Arnold was an enthusiastic patriot who believed passionately in the cause of American liberty. It is what happened after 1775 that began to wear him down and bring on his disillusionment. In his martial success, he became the target of jealous mediocrities.

Two examples: After Arnold pulled off a magnificent defense of Lake Champlain in October 1776 that caused the British to call off their invasion from Canada that year, Gen. William Maxwell of New Jersey publically faulted Arnold for wasting the naval fleet, as if the idea was to save the vessels and let the British invade. A Congressman wrote Arnold while he was on Lake Champlain warning him about petty backbiting directed toward him in Congress, to the effect that your best friends are not your countrymen. Being passed over by Congress in Feb. 1777 for a very deserved promotion that Washington thought Arnold should have had (to major general) was a complete insult to Arnold’s honor as a gentleman. George Washington agreed but urged Arnold not to resign. Benedict Arnold didn’t and brought the victory at Saratoga, with piker Horatio Gates getting the public credit.

Wounded seriously twice, a near cripple the rest of his life, Benedict Arnold, as just noted, started to have serious doubts about the cause even before he met the bewitchingly beautiful Peggy Shippen.

And what about all these stories about his young wife Peggy Shippen urging him to switch sides?

My opinion, a misrepresentation of the evidence.

In June 1778, George Washington, knowing the recovering Benedict Arnold could not take a field command, named him the military governor of Philadelphia. This brought Arnold into contact with the nominal head of Pennsylvania’s government, Joseph Reed. Reed was one of those people who could find something to dislike in everyone else but himself. Reed, in fact, had bad mouthed Washington as a bumbling commander while serving him as an aide back in 1776. He wanted to get even with suspected tories in Philadelphia who had aided the British during their occupation of the city (September 1777-June 1778).

Reed resented Arnold’s imposition over the city, with orders that Benedict Arnold received from Washington to stabilize the situation and avoid needless retribution directed toward those in the city who had supposedly collaborated with the British. Peggy’s family was more neutral than loyalist, despite what has been written. Benedict Arnold met Peggy and fell in love with her (Arnold lost his first wife to an early death back in 1775). Peggy in turn felt attracted to this man who was twice her age. Reed saw it as Arnold playing up to the very loyalist types he wanted to punish. So Arnold and Peggy married in April 1779, much to the chagrin of Reed and his followers. And for many writers, Peggy took over and played the role of Eve feeding the great hero Benedict Arnold the poison fruit. In reality, determined to get Benedict Arnold, Reed trumped up several charges against him that attacked Arnold’s honesty, character, and reputation.

These charges became public around the time of their marriage, and Benedict Arnold had finally had enough. What Peggy had were contacts with British officers, including John Andre, and it’s my opinion that she offered those contacts to Benedict Arnold whose anger led him to begin communications with the British. As such, the record really has no basis for showing Peggy as the corrupting biblical Eve, although she had to know what was going on.

What triggered Arnold’s court martial and formal rebuke in 1780? What did Washington think about all this?

The court martial was in response to the eight charges lodged against Benedict Arnold by Reed and his followers. Arnold demanded satisfaction, but Congress refused to support him, and Reed, I think to purposely torture Arnold, kept asking for delays so he could gather evidence to prove his charges, which makes one wonder why he didn’t seem to have evidence before making the charges (charges filed back in early 1779 but the court martial didn’t take place until Dec. 1780-Jan, 1781).

Benedict Arnold was acquitted of all charges except two: allowing a vessel to clear port in Philadelphia when the port was closed (Arnold had an investment in the vessel and the trade goods it was carrying). And the other charge was using public wagons to move trade goods belonging to him. (Benedict Arnold did acknowledge this charge and was paying for their use).

As for George Washington, he went along with Reed’s incessant delays because Reed kept threatening that he would not call out the Pennsylvania militia to support Washington’s martial efforts if he was not given time to dig up evidence (Washington was actually trying to help Arnold but couldn’t because he thought he needed the troop strength).

The court martial hearing board recommended to Congress that Benedict Arnold be publicly reprimanded and gave the assignment to Washington, who did so only in orders of the day. But that was it. To Arnold, now even Washington seemed like an enemy. Trying to ameliorate matters, Washington offered Arnold command of a wing of the Continental army. But Arnold insisted on the West Point command, and the rest is history.

There was no turning back for Benedict Arnold once that reprimand took place. Disillusionment had morphed into bitterness. Arnold firmly believed that the patriot cause had ruined him and his good name, despite giving his all, including his good health and much of his personal fortune. Stated differently, Arnold believed that Washington and the cause had betrayed him.

Is there a specific point where Arnold clearly becomes a traitor to the American cause?

Key points include his being passed over (stupidly I might add and George Washington would agree) for promotion to major general in February 1777; seeing Congress, a body Benedict Arnold increasingly despised, turn Gates undeservedly so into the “hero of Saratoga”; recuperating from a terrible wound after Saratoga and then having to put up with the likes of Joseph Reed and his attacks on Arnold’s character in Philadelphia; and the court martial experience and reprimand by Washington in the late winter of 1781. There was no turning back. Benedict Arnold told Major John Andre in correspondence that the American cause was in its death throes, and Arnold hoped he might lead the rebels back into the British fold. He was very wrong on that latter count.

What actions did Washington and the Continental Army take once they found out about Arnold’s treachery?

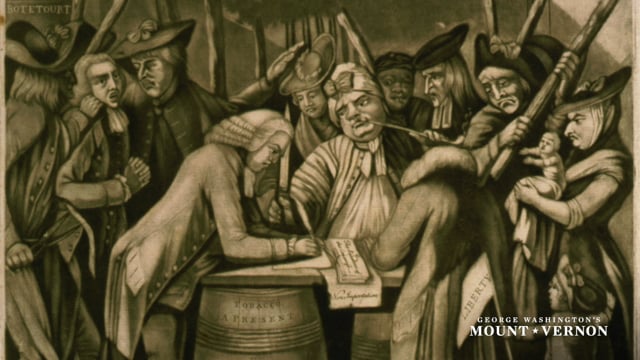

“Treason of the blackest dye” was the message spread far and wide by George Washington and other leaders in the Continental Army. Benedict Arnold would be denounced at every turn, mostly as a money grubbing agent of Satan himself. There would be parades in some communities, such as Philadelphia, devoted to renouncing any value in or contributions to the cause by Arnold (this did take some active rewriting of the actual historical record).

Very good images of the float devoted to Benedict Arnold, two-faced and selling himself to the devil for filthy lucre still exist. Look at p. 9 of my Arnold biography for some interesting descriptions, all of which are negative. On Oct. 4, 1780, the Continental Congress struck Benedict Arnold’s name from the record of general officers serving in the Continental Army. In particular, since the cause had become for all practical purposes stagnant at this time, Washington worried lest there were other Arnolds out there. So he skillfully used Benedict Arnold’s alleged perfidy once again to rally the general populace to the cause. As such, Benedict Arnold’s name took a beating from which his reputation has never recovered.

Few realize that Arnold became a field general for the British Army during the war. What actions did Arnold and his troops undertake?

Yes, he did receive a brigadier’s commission and led two British attacks, one on Virginia in early 1781, and one on New London, CT, in September 1781. Accounts of these raids are full of lurid and exaggerated details, literally down to today. Benedict Arnold took it easy on the Virginians and focused on destroying legitimate military targets. Events in New London, a major center of American privateering activity that was adversely affecting British supply lines back to England, got out of hand, and much of the that town was burned to the ground. Benedict Arnold denouncers, of course, then and still now see Arnold’s evil hand at work in these events.

He and Peggy soon sailed for England after these raiding ventures, pretty much ending Arnold’s military career.

Benedict Arnold, even in the 21st century, is seen as the definition of an American traitor. How do you think we should view Arnold today?

Benedict Arnold is having somewhat of a comeback. His contributions to the cause of liberty are no longer being swept under the table. There’s really not much evidence to prove that selling out West Point, had the British taken this post, would have made much of a difference in the Revolution’s outcome.

Further, Benedict Arnold serves as a key component in moving beyond good guys-bad guys history in which all Americans are good and all British participants (and loyalists) are bad. The American cause was not wholly pure and the British side corrupt. Too often the Revolution has been treated as some sort of morality play–good versus evil. Both sides had their share of each, even though many in modern America still prefer the moralistic version of historical reality during the Revolutionary era.

If nothing else, analyzing the life of Benedict Arnold, just as much as studying the life of Washington, brings out the complexities and human difficulties during which the new American republic, after incredible human struggles, came into being among the nations of the world.