Washington's first 100 days stretched from his inauguration on April 30 to August 7, 1789. Taking some license, we can expand the period to the end of the first session of the First Federal Congress on September 29, technically 153 days. By this measure, no president accomplished more at the start of their presidency than George Washington.

By the end of this period, the new government had passed the Bill of Rights; established the principle of national taxation; designed the nation's court system; and created the first executive departments. This list of accomplishments is remarkable, but it does not even include the greatest achievement of Washington's first one hundred days: he established the very office of president, thereby giving legitimacy to the new federal government under the Constitution.

Few, who are not philosophical Spectators can realise the difficult and delicate part which a man in my situation had to act ... I walk on untrodden ground. There is scarely any action, whose motives may not be subject to a double interpretation. There is scarely any part of my conduct w[hi]ch may not hereafter be drawn into precedent.

Washington to Catherine Sawbridge Macaulay Graham, January 9, 1790

Day 1

Inauguration in New York City

On the morning of the 30th, George Washington dressed in a suit of brown broadcloth spun in Hartford, with buttons displaying an eagle with wings spread.

The president-elect was escorted by numerous representatives to Federal Hall about half past noon. Upon arriving, he entered the Senate chamber where the two houses of Congress awaited their new head of state. Robert Livingston, Chancellor of New York, administered the oath, and Samuel Otis, Secretary of the Senate, held the ceremonial Bible.

From the portico overlooking Wall and Broad Streets, Livingston turned to the teeming streets below and shouted, "Long live George Washington, President of the United States!" After taking the oath of office on the balcony of Federal Hall, President Washington went back inside the Senate Chamber to deliver his inaugural address.

I was unable to attend to any business whatsoever; for Gentlemen, consulting their own convenience rather than mine, were calling from the time I rose for breakfast --often before-- until I sat down to dinner.

Washington to Stuart, July 26, 1789

Congratulations "not to yourself, but to my country" from Thomas Jefferson

"...permit me to express here my felicitations, not to yourself, but to my country... nobody who has tried both public & private life can doubt but that you were much happier on the banks of the Patowmac than you will be at New York. but there was nobody so well qualified as yourself to put our new machine into a regular course of action. nobody the authority of whose name could have so effectually crushed opposition at home, and produced respect abroad. I am sensible of the immensity of the sacrifice on your part. your measure of fame was full to the brim: and therefore you have nothing to gain."

Letter to the House of Representatives

"Gentlemen, Your very affectionate Address produces emotions which I know not how to express. I feel that my past endeavours in the Service of Country are far overpaid by its goodness: and I fear much that my future ones may not fulfil your kind anticipation. All that I can promise is, that they will be invariably directed by an honest and an ardent zeal. Of this resource my heart assures me. For all beyond, I rely on the wisdom and patriotism of those with whom I am to co-operate, and a continuance of the blessings of Heaven on our beloved Country."

Determining Public Forums for the President

Washington involved Congress and a close circle of advisers in the process of making his public schedule. On May 10, he delivered a questionnaire to the Senate about the appropriate public forums for the president.

Washington soon also polled the House, Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Jay, and diplomat Robert R. Livingston. From the outset, he tried to strike a balance, concluding that the president must "allow him[self] time for all the official duties of his station" while at the same time taking care "to avoid as much as may be, the charge of superciliousness, and seclusion." Washington used the responses to his inquiries to help create a schedule of regular public and private appearances.

Advice from Alexander Hamilton on "the demeanour of the Executive"

"Men's minds are prepared for a pretty high tone as in the demeanour of the Executive; but I doubt whether for so high a tone as in the abstract might be desirable. The notions of equality are yet in my opinion too general and too strong to admit of such a distance being placed between the President and other branches of government as might even be consistent with a due proportion. The following plan will I think steer clear of extremes and involve no very material inconvenainces."

I beg you to accept my unfeigned thanks for your friendly communications of this date-and that you will permit me to entreat a continuation of them as occasions may arise. The manner chosen for doing it, is most agreeable to me. It is my wish to act right; if I err, the head & not the heart, shall, with justice, be chargeable.

Washington to Alexander Hamilton, May 5, 1789

Letter from Cherokee Nation, Signed by 24 Native Americans

"We rejoice much to hear that the great Congress have got new powers and have become strong. We now hope that whatever is done hereafter by the Great Council will no more be destroyed and made small by any State. We shall always be ready to listen with open ears and willing hearts to you or any one joined with you and to no other for protection, and regulating all matters."

First Lady Martha Washington Arrives in the Capitol

Almost as soon as she arrived, Martha Washington was swept up in the new duties of her position. She was not only responsible for managing the presidential household but also for supervising the domestic affairs at Mount Vernon from a distance.

Each day, she was expected to dress formally, receive visitors, and make calls on important members of society. This was not how Martha would have preferred to live. Although she maintained her calm, cheerful, and dignified demeanor, she felt she was (as she told her niece) “more like a state prisoner than anything else.”

I thank god the Prdt [sic] is very well, and the Gentlemen with him are all very well, -- the House he is in is a very good one and is handsomely furnished all new for the General-- I have been so much engaged since I came hear.. I have not had one half hour to myself since the day of my arrival...

Martha Washington to Fanny Bassett Washington, June 8, 1789

Washington Supports Madison's Bill of Rights

James Madison faced skepticism in the Federalist-dominated Congress that the amendments, originally an Antifederalist idea, were necessary. President Washington wrote a letter to Madison, which was shared in Congress, that the amendments "have my wishes for a favorable reception in both houses."

As far as a momentary consideration has enabled me to judge, I see nothing exceptionable in the proposed amendments. Some of them, in my opinion, are importantly necessary; others, though of themselves (in my conception) not very essential, are necessary to quiet the fears of some respectable characters and well meaning men. Upon the whole, therefore, not forseeing any evil consequences that can result from their adoption, they have my wishes for a favourable reception in both houses.

Washington to James Madison, May 31, 1789

Day 50

First Bill Under the Constitution is Passed

The president signed the first bill passed under the Constitution, a measure to regulate the administration of oaths.

Gets a Full Account of the Domestic Debt

The Board of the Treasury apprises President Washington of the current financial situation of the new nation.

Washington Library Director Douglas Bradburn on the Economy After the Revolutionary War

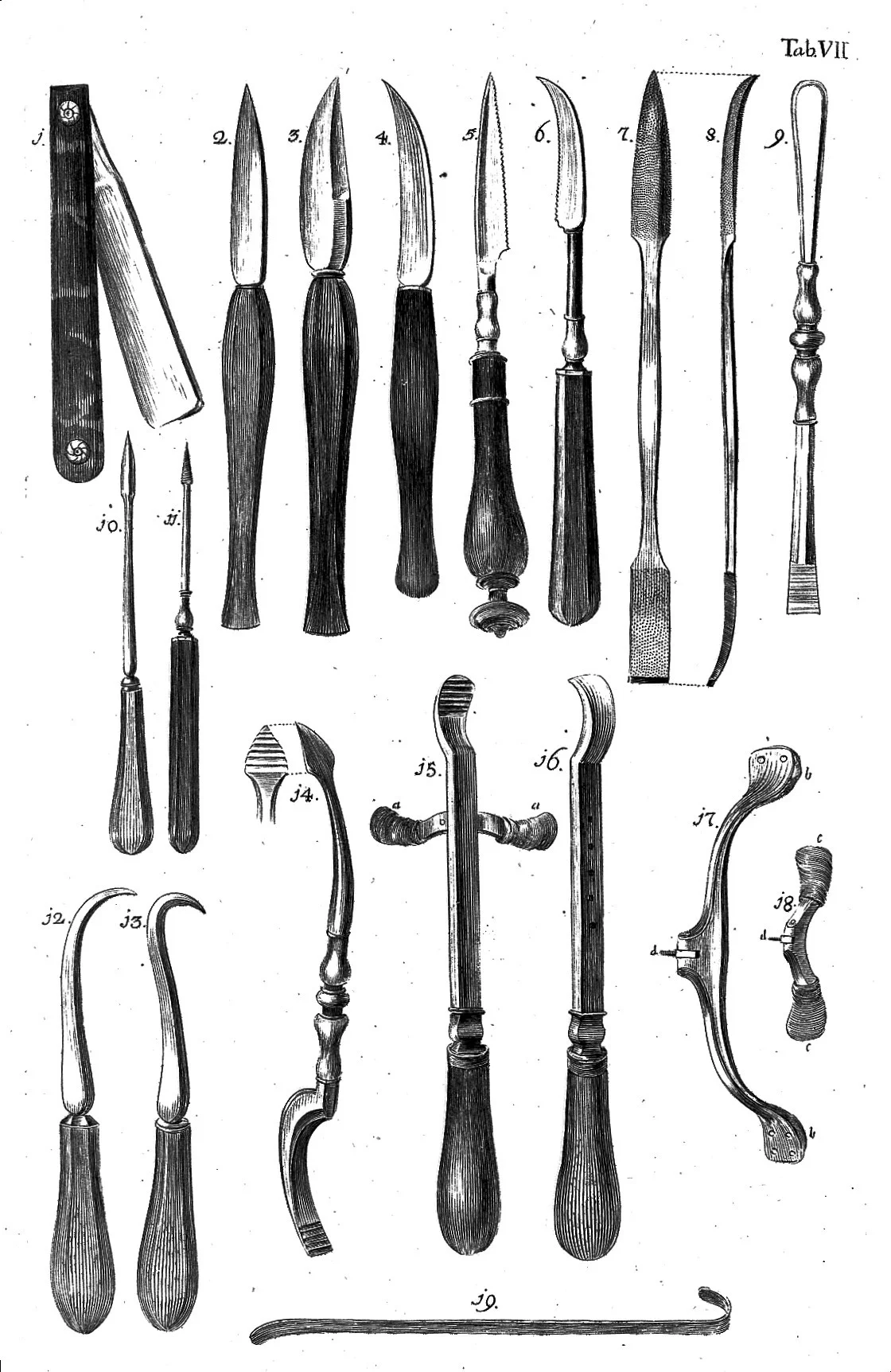

Bacterial Infection Requires an Emergency Surgical Procedure

In mid June, President Washington develops a severe fever which is soon attributed to an emerging growth on his left thigh. He was seriously ill for several weeks, although the extent of his incapacitation was not shared publically.

Washington was under the care of Dr. Samuel Bard, one of the city's leading physicians. Dr. Bard initially diagnosed the president's illness as anthrax, and ultimately determines that the tumor would require surgery immediately.

Aided by his father, Dr. John Bard, the operation was conducted on June 17, 1789. The president responded well to Bard's treatment, although he remained confined to his bed and suffered from severe weakness. It was not until almost a month later that Washington was able to return to business at a reduced capacity. On July 3, Washington writes: "... my health is restored, but a feebleness still hangs upon me."

Tariff Act of 1789

Congress spent much of June and July of 1789 working to establish sources of revenue for the new government. On the symbolic date of July 4, President Washington signed the Tariff Act of 1789. The law placed a five percent tax on all imports.

Update from the War Office, Indian Department, Southern District

Secretary of War Henry Knox informs President Washington about the status of the Creeks, a group of Native Americans who reside in regions across Georgia and Spanish controlled territory.

He informs that "The State of Georgia is engaged in a serious war with the Creeks and as the same may be so extended to require the interference of the United States". There were a total of three treaties signed with this group, which Knox informs Washington that "The Creeks object entirely to the validity of the said treaties."

The disgraceful violation of the Treaty of Hopewell with the Cherokees, requires the serious consideration of Congress. If so direct and manifest contempt of the authority of the United States be suffered with impunity, it will be in vain to attempt to extend the arm of the Government to the frontiers...

Henry Knox to Washington, July 7, 1789

Writes Letter Congratulating Namesake College

Washington College, which was founded in 1782, had gained a good reputation, and considerable importance in its location in in a port city. George Washington, who had consented to the fledgling college's use of his name, extended his warm wishes for the "lasting and extensive usefulness" of the institution. He also expressed his belief that a good public education system was essential in the new nation: "... in civilized Societies the welfare of the State and happiness of the People are advanced or retarded in proportion as the morals and good education of the youth are attended to"

Blocks Spam

Hodge, Allen, and Campell, who represent a publication called History by Dr. William Gordon, write to President Washington and "humbly beg the privilidge to dignify our list of Subscribers, which is very numerous, by adding Your respectable Name thereto".

Washington declines: "As I have already several sets of that work I would wish to decline adding my name as a subscriber for more."

Senate Votes on President's Removal Power

The Senate's vote on the president's removal power ended in a tie, which was broken by Vice President John Adams.

Worrisome News from Fredericksburg

Betty Lewis, George Washington's only sister, shares an update on the failing health of their mother, Mary Ball Washington, who was struggling with breast cancer. "I am sorry to inform you My Mothers Breast still Continues bad. God only knows how it will end; I dread the Consequence." Betty suggests to her older brother that "the Doctors think if they Could get some Hemloc it would be of Service to her Breast, if you Could Precure som there."

Washington Rejects His Nephew's Appointment Request

Washington held all potential appointees to the same high standards, regardless of their connection to him. His nephew, Bushrod Washington, asked his uncle for the position of United States attorney for Virginia. Washington rejected Bushrod's request because he was not as well qualified as other lawyers in the state.

"My political conduct in nominations," Washington explained, "must be exceedingly circumspect and proof against just criticism."

I believe I need not say that the most delicate-and in many instances, the most unpleasing part of my administration, will be the nomination to offices. Notwithstanding I have entered upon this novel and arduous business, unbound by a single engagement-and, so far as I know my own heart, uninfluenced by any ties of blood or friendship, yet I am well assured I shall find no small difficulty in advancing such characters only to office as will give universal, or general satisfaction.

Washington to Nathaniel Gorham, May 9, 1789

Established the Department of Foreign Affairs

Known today as the Department of State.

Washington Almost Vetoes a Bill

This bill addressed the difficult question of how to assess duties according to the tonnage (carry capacity) of vessels.

President Washington and his cabinet felt that nations which interfered with or discriminated against America trade, such as Britain, should face higher tonnage duties. James Madison's efforts at incorporating this principle into the final bill failed. When the bill reached Washington's desk, the president faced a choice: sign an imperfect bill or use his veto power for the first time.

Washington did not take the decision to use the veto lightly. Having learned that Congress was already considering revisions to the proposed tonnage policy, Washington signed the imperfect bill into law to avoid a needless confrontation.

... in confidence I can assure you --with the world it would obtain little credit-- that my movements to the chair of Government will be accompanied with feelings not unlike those of a culprit who is going to the place of his execution: so unwilling am I, in the evening of a life nearly consumed in public cares to quit a peacful abode for an Ocean of difficulties, without that competency of political skill-abilities & inclination which is necessary to manage the helm.

Washington to Henry Knox, April 1, 1789

Senate Rejects Washington's Nomination

The president twice clashed with senators over the advisory power of the Senate. The first confrontation took place when the Senate rejected Washington's nomination of Benjamin Fishbourn as collector of the Port of Savannah. President Washington visited the Senate chamber in Federal Hall to express his displeasure.

Senator James Gunn of Georgia confessed that he had blocked the nomination. Though upset, Washington did not pursue the matter any further. The case provided the foundation of "senatorial courtesy," whereby senators reserve the right to block nominations in their home states.

Day 100

Curator Amanda Isaac on Fashion Statements by the First Lady

I live a very dull life hear and know nothing that passes in the town - I never goe to the publick place - indeed I think I am more like a state prisoner than anything else, there is certain bounds set for me which I must not depart from - and as I can not doe as I like I am obstinate and stay at home a great deal

Martha Washington to Fanny Bassett Washington, October 23, 1789

Established the Department of War

Known today as the Department of Defense.

Senate Asserts Role of "Advise and Consent"

The president and senators collided over the Senate's constitutional role to "advise and consent" in the making of treaties.

Aside from the two-thirds vote necessary to approve treaties, it was unclear what role the Senate should play in treaty negotiations. Ever faithful to the Constitution, Washington interpreted the document to mean that he should appear in the Senate to collect opinions from senators on specific treaty provisions. On August 22, Washington did just that in the middle of his administration's negotiations with southeastern Indian tribes over borders and other issues.

Individual senators asked to have Washington's questions reread, insisted on more information, and explored the possibility of forming committees. The longer the debate went on, the more irritated Washington became. He eventually declared, "This defeats every purpose of my coming here," and soon left. Ever since, the Senate's power to advise and consent has come to mean something short of direct participation in the treaty-making process.

In arriving at this interpretation, Washington was careful not to overstep his constitutional authority. When the president's diplomatic emissaries concluded the same treaty that had triggered Washington's visit to the Senate, his cabinet advised that he could withhold whatever materials he deemed harmful to the national interest or his own executive power.

Washington decided to submit all papers related to the treaty to the Senate. He continued to keep the Senate informed about future treaty negotiations and provided all materials requested, stipulating only that the body review information that could jeopardize the national interest in closed session. It was this spirit of cooperation that made possible the legendary accomplishments of the First Federal Congress.

Mary Ball Washington Dies of Breast Cancer

Mary Ball Washington finally succumbs to breast cancer, just over two years after being diagnosed with the affliction. President Washington's brother-in-law, Burgess Ball, shares the sad news about their mother: "I am sorry that it devolves on me to communicate to you the loss of your mother who departed this life about 3 o’clock today. The cause of her dissolution (I believe), was the cancer on her breast, but about for 15 days she has been deprived of her speech, and for the last five days, she has remained in a sleep."

Washington writes to his sister Betty Lewis after hearing the news of their mother’s death, finding comfort in their mother’s long and full life. "Awful, and affecting as the death of a parent is, there is consolation in knowing that Heaven has spared ours to an age, beyond which few attain, and favored her with the full enjoyment of her mental faculties, and as much bodily strength as usually falls to the lot of four score. Under these considerations and a hope that she is translated to a happier place, it is the duty of her relatives to yield due submission to the decrees of the Creator…"

Established the Department of the Treasury

Hamilton Appointed as Secretary of Teasury

President Washington appointed Alexander Hamilton as the first United States Secretary of the Treasury. He left office on the last day of January 1795.

The eyes of America -- perhaps the world -- are turned to this Government...

Washington to David Stuart, July 26, 1789

Knox Appointed Secretary of War

President Washington appoints Henry Knox as the first United States Secretary of War. He left office on December 31, 1794.

Ron Chernow on Washington's Presidential Cabinet

Signs the Judiciary Act of 1789

On September 24, Washington signed the Judiciary Act of 1789, which created the federal court system, the office of Attorney General, and the six-member Supreme Court.

Bills of Rights

Congress approved twelve amendments to the Constitution and submitted them to the states for ratification. The states ratified ten of them, which became the Bill of Rights.

Washington did not usually involve himself in the legislative process but the Bill of Rights proved an important exception. Throughout his first 100 days, he continually promoted the principals of the First Amendment, particularly the free exercise of religion. Ultimately, he exchanged salutations with 22 different religious groups, including persecuted groups such as Jews, Quakers, and Catholics. To each, he pledged the support and protection of the U.S. government.

... no one would be more zealous than myself to establish effectual barriers against the horrors of spiritual tyranny, and every species of religious persecution.

Washington to the United Baptist Churches of Virginia, May 1789

Day 150

First Federal Congress

The First Federal Congress, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives, convenes at Federal Hall in New York City.

Washington Library Director Douglas Bradburn on the Acts of Congress

George Washington's copy of the Acts passed at a Congress of the United States of America (New-York, 1789) contains key founding documents establishing the Union: the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and a record of acts passed by the first Congress.

The most significant features of this book are Washington’s personal notes, penciled in the margins. All of his notes in this volume appear alongside the text of the Constitution, where he drew neat brackets to highlight passages of particular interest.

... the national government is organized, and, as far as my information goes, to the satisfaction of all parties -- that opposition is either no more, or hides its head.

Washington to Gouverner Morris, October 13, 1789