In her youth, Martha Washington wore audacious yellow silks, purple slippers, and accessorized with glittering gems. Style was no stranger, and Martha proved a leader amongst the fashionable elite of Virginia. And she had the lace to prove it.

![Portrait of Martha Dandridge Custis, John Wollaston, oil on canvas, 1757. Washington-Custis-Lee Collection, Washington and Lee University, Lexington, VA. [U1918.1.1]](https://mtv-drupal-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/files/resources/mrs-daniel-parke-custis.jpg?VersionId=37UyNZ5TArbcoxkSEJ64QMoQty2o.dC0)

Lace was the ultimate glamor accessory—akin to sporting a Hermès Birkin bag today or, for a more timeless example, unabashedly draping oneself with ropes of diamonds.

Let’s take a look at how lace in the 18th century was the ultimate power accessory and how Martha Washington communicated personal values through her wearing of this exquisite art form.

Lace in the 18th Century

Sarah Woodyard, Journeywoman Milliner at the Margaret Hunter Shop, tells us about lace, how it was worn, the different kinds, and who wore it in the 18th century.

All lace in the 18th century generally derived from two techniques:

Who Made Lace?

In 18th-century France and Flanders, men designed the lace patterns, while women served as the lacemakers. Lace was made in manufactories, or “centers." Probably prized for their diminutive, nimble fingers and developmental agility in forming muscle memory, children were trained to become lacemakers at very young ages, some even as young as 5 years old.

On “Point” and For Power: The First Lace

Lace as we know it today originated in medieval Europe when the edges of robes were cut in patterns of leaves and flowers and bound, sometimes with gold thread. The word “lace” originally meant a length of silk cord that was used to tie together sections of clothing, such as a woman’s sleeve to her bodice. Lace was also often frequently referred to as “point”—either for the needlepoint construction technique or for the metal encasements usually found at the end of laces to keep them from fraying.

Two regions claim to be the birthplace of lace—Italy and Belgium. Though both assertions of fame are valid, Belgium contributed a great deal to the arena of thread lace, while Italian inventories were the first to have documented mention of lace[1].

The Church

In one of its earliest uses, lace served as a symbol of power for the Church. Statues of saints and the Virgin Mary were draped with the finest lace, as were the ecclesiastical vestments for the papal court, often boasting intricately designed Christian iconography. From towels used for service on the altar to the albs (gowns) of priests, this rich, costly, and visually stunning adornment communicated the might and authority of the Catholic, and later, Anglican faith.

Changes in Lace Trends

Like fashions today, the style of lace changed over the course of the 18th century. Lace from the earlier part of the century had a more “baroque” feel, meaning that the patterns on lace were very bold, and heavy designs completely filled the background. As the century progressed, lace began to reflect the qualities of the rococo period, meaning that lace patterns were more ethereal and elegant, and the mesh ground was more visible. At the end of the century, lace reflected neoclassical influences through designs of increasingly simplistic elegance.

Popular Types of Lace in the 18th Century

| Type | Technique | Description |

| Mechlin | Bobbin | Pronounced “meck-lin”, this lace was known as the “Queen of Laces” – the lace of royalty, made famous by the French court. It is also known by its French name, point de Malines. Martha Washington’s wedding lace is Mechlin lace. |

| Valenciennes | Bobbin | Although named for the French town of Valenciennes, this delicate lace traces its roots to Flanders. It is known for its durability due to the number of twists in the braided mesh. |

| Chantilly | Bobbin | Chantilly, a suburb of Paris, dates lace production to the days of Louis XIV. One of the celebrated laces of royalty, this perennially fashionable lace endured even past the 18th century to the days of Napoleon III. |

| Alençon | Needlepoint | Louis XIV established a strong lacemaking industry in France in the late seventeenth century and granted Alençon, sixty miles northwest of Paris, the honor of producing lace. An elaborate lace with exquisite detailing, it originated as a replication of Venetian techniques. |

Looking at Lace

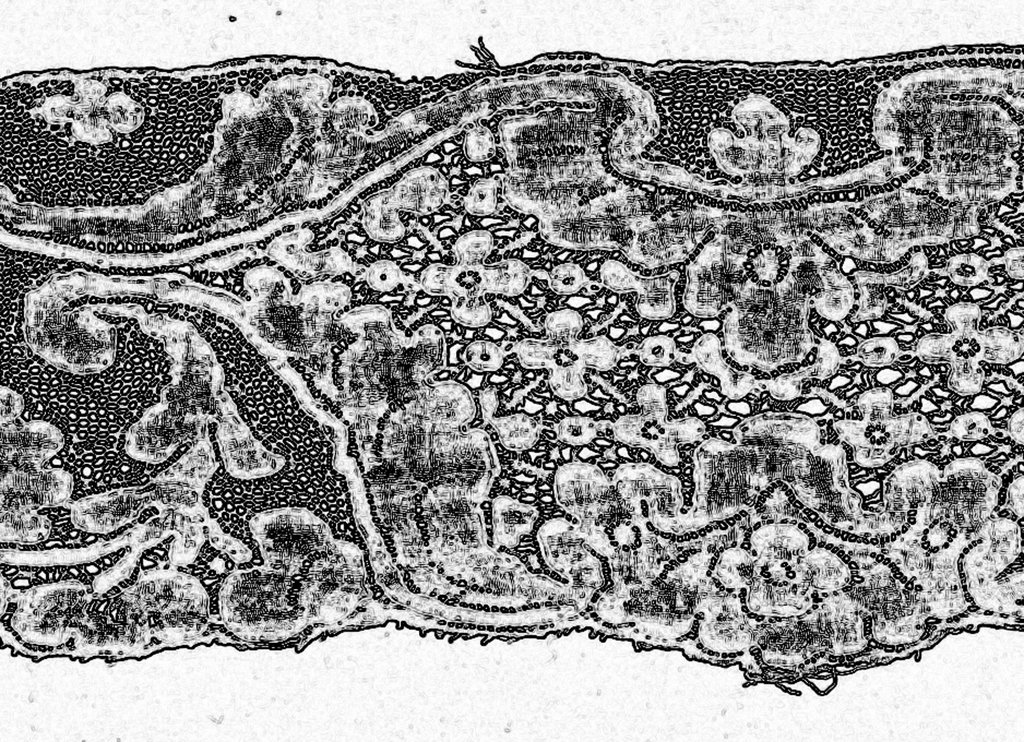

A Sample of Laces in the Mount Vernon Collection

The laces featured below from the Mount Vernon collection have a Washington provenance.

Lace Fit for a Queen…or Martha Washington

European royalty and the noble elite conspicuously draped themselves in the richest and most lavish of lace in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. Wardrobe inventories for Henry VIII of England indicate that he had sleeve ruffles, neck cuffs, and other lace-bedecked adornments.[2] In Queen Elizabeth I’s day, the prevailing fashion was for enormous, magnificent lace neck ruffs stiffened by starch. In 1713, Queen Anne’s bill for Brussels and Mechlin lace was £1418, 14s—to one lace merchant alone.[3] A modern-day monetary equivalent would be well in the tens of thousands of dollars for such an extravagant purchase.

The lace from the shoulder to the skirt hem of the woman’s gown, as well as several sets of lace cuffs, make a bold statement on family wealth, prestige, and power. John Jennings, Esq. with his Brother and Sister-in-Law 1769 by Alexander Roslin (Wikimedia Commons)

In the American colonies, Martha Washington’s taste in lace was also very courtly—but she employed her ideals of elevated style with both sense and discrimination. She had the means to purchase the finest goods available, and yet her purchases were judiciously tempered by an understanding of the need to communicate sophistication over ostentatiousness. Her choice of bridal lace is the finest Mechlin, of the same seen on the necklines and sleeves of many a European royal—but worn with elegant subtlety.

Ipswich Lace: American Industry Meets Patriotic Pretty

Europe was not the only lacemaking center during the 18th century. From 1750-1840, Ipswich, Massachusetts, is the only location in America that had a successful commercial lacemaking enterprise. American embargoes against all English imported luxury goods began in 1760, and many women in the colonies began to show a strong and patriotic inclination to support domestic manufactories. So well-reputed, and successful, was this New England lacemaking center that on December 5, 1791, after given samples of lace, Alexander Hamilton addressed Congress on Ipswich’s accomplished and excellent lacemaking.

Object records at Mount Vernon indicate that Martha Washington owned a black lace shawl made from Ipswich lace. Handed down through the generations, the lace shawl was refashioned into a later style and then placed on a cotton ground, or backing, to stabilize the lace’s significant damage.

Primary Source

The primary source below indicates Martha Washington’s desire for value and quality in her lace purchases, her dissatisfaction with a prior purchase, and yet another order for more lace.

To Mrs. S. Thorpe, Milliner in London, July 15, 1772

I cannt. help writing to you in behalf of my daughter, Miss Custis, who together with myself, Imported some very hard bargains from you last year. Messrs. Cary & Co. was wrote to for a handse Suit of Brussels Lace to cost £20, in cons of wch., she recd. from you a pr of tripple Ruffles, a Tucker & Ruff set on plain joing. Nett (such as can be bought in ye Milliners Shops here at 3/6 pr yd) When, if you had ever sent a Tippet & Cap w. ye othr. things I shd still have thot them Dr. – These things have been shewn to sevl. Ladies who are accustomed to such kind of Importns, & all agree, that they are most extravagantly high charged.

I now sd for a suit of ye price of £40; w. Lappels & ca but if you cant afford to sell a much better bargn. in these, that yo. did in ye last I shd hope yt Mr. Cary will try elsewhere, as I thy her last add. To my own is worth a little pains – and ye. othr. things sent last year for myself &ca were 5 gauze Caps. W Blond Lace bordrs. at a Ga. each, when ye same kd. might have been bot in ye Country at a much less price. – I have now sent for 2 Caps for M. Custis & 2 for myself of Mint. Lace & wd have ym gentl but not espens. her to suit a Person of 16 yrs old mine one of 40 & I cant. help addig. that I thnk it neccesy that ye last yrs Suit (wch ought to be retd. If she cd. do witht in the ye meanwhile) shd be compld w. a Tippet & Cap, as it is Scae more yn 1/3 a (?).

I am Madm yr Hble Servt

Martha Washington

Antique & Estate Jewelry

Explor our unique collection of estate and antique jewelry.

Sources and Further Reading:

Brady, Patricia. Martha Washington: An American Life. New York: Penguin Books, 2005.

Breen, T. H. The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

C. F. W. 1923. “A Flounce of Point De France Lace”. Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum 19 (81). Philadelphia Museum of Art: 49–50.

C. F. W. 1923. “A Unique Example of Mechlin Lace”. Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum 18 (73). Philadelphia Museum of Art: 13–15.

Chernow, Ron. Washington: a Life. New York: Penguin Books, 2011.

DuPlessis, Robert S. The Material Atlantic: Clothing, Commerce, and Colonization in the Atlantic World, 1650-1800. London: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Earnshaw, Pat. The Identification of Lace. 2nd ed. Aylesbury, Bucks: Shire Publications, 1984.

Earnshaw, Pat. Lace in Fashion: from the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Centuries. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd., 1986.

Fields, Joseph E., ed. Worthy Partner: the Papers of Martha Washington. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1994.

Haulman, Kate. The Politics of Fashion in Eighteenth-Century America. North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Kurella, Elizabeth M. The Secrets of Real Lace. Plainwell, MI: Lace Merchant, 1994.

Levey, Santina M. Lace: a History. Victoria & Albert Museum, London: W. S. Maney & Son Limited, 1983.

“Letters of Rev. Jonathan Boucher.” 1912. Maryland Historical Magazine Baltimore, Maryland: The Maryland Historical Society, (5).

Moore, N. Hudson. The Lace Book. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1904.

Raffel, Marta Cotterell. The Laces of Ipswich: the Art and Economics of an Early American Industry, 1750-1840. Hannover: UPNE, 2003.

Schlesinger, Arthur M. 1962. “The Aristocracy in Colonial America” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society. The Massachusetts Historical Society 2 (74). 3–21.

Standen, Edith Appleton. 1958. “The Grandeur of Lace”. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 16 (5). The Metropolitan Museum of Art: 156–62.

Simeon, Margaret. The History of Lace. London: Stainer & Bell Ltd, 1979.